While some Star Trek fan films have begun to Artificial Intelligence ( A.I.) in limited ways to age and de-age characters and also to create brief visuals and short bits of dialog, my new animated fan film AN ABSENT FRIEND is the first time that A.I. speech synthesis has been used to generate ALL of the voices. And what’s more, two of those voices are sampled from the late LEONARD NIMOY and DeFOREST KELLEY, allowing the beloved characters of Spock and McCoy to live on.

The obvious question that might come to mind for some people would be: Is this legal? The short answer is “yes…at least for now.” That could change in the not-too-distant future, but no law governing or restricting the A.I. generation of a deceased actor’s voice in a fan film exists at the moment. I will dive more deeply into the legal status of voice A.I. in Part 3 of this blog series (along with the ethical considerations). However, right now in Part 1, I would like to discuss how I managed to digitally recreate the voices of these two deeply-missed actors, and in Part 2, I’ll be covering how I and my illustrator, MATT SLADE, turned an audio drama into a full animated Star Trek fan film.

First, though, let’s take a look at this groundbreaking project…

ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE TAKING OVER THE WORLD?

A.I. has exploded across the planet in the last year and a half, and it’s certainly become a bit of a mixed bag. The term itself is an umbrella for a wide range of digital breakthroughs whereby computers are doing some incredible—and occasionally worrisome—things. A.I. is being used for everything from generating business presentations and news articles to writing millions of lines of computer code in seconds. A.I. digitally de-aged an 80-year-old HARRISON FORD in the fifth and final Indiana Jones feature film last year and also completed an unfinished Beatles song despite two of the original band members having died decades ago.

Law enforcement is using intuitive software to sift through endless social media postings to track down wanted suspects and potential terrorists. On the other side of the moral spectrum, however, some students are using A.I. software to write their school essays for them, while a few political campaigns have begun to generate false images and articles to spread realistic-looking fake news to unsuspecting voters. Earlier this year, a New Hampshire robocall seemingly from Joe Biden that told Democrats not to “waste their vote” in the primary was actually faked by a supporter of one of the other primary candidates. And of course, the recent Hollywood writers and actors strikes worried that A.I. would make many of their jobs all but irrelevant.

My own mind was blown last year when I saw A.I. used to create an actual Star Trek fan film! THE RODDENBERRY ARCHIVE released the following short fan film featuring a deepfaked face of Leonard Nimoy as Spock put onto the body of actor LAWRENCE SELLECK…

Unbelievable, right? I certainly thought so! And it actually inspired me (at least indirectly) to utilize A.I. myself to bring a fan film idea of my own to life.

I first wrote the script that would become AN ABSENT FRIEND back in 2010 as an entry into a Star Trek short story contest (which I won). Originally titled “You’re Dead, Jim” (I never really liked that title), it was more of a script for a two-man stage play, inspired by the comic book Star Trek: Spock – Reflections where Spock brings James Kirk’s body back to Iowa from Veridian III where Picard buried him.

My story, however, took place 78 years earlier, just after Kirk’s apparent death saving the Enterprise-B. It looks at the very different reactions of Bones and Spock as they discuss the death of their friend in a San Francisco bar. It also addressed a couple of “incongruities” in Trek lore, including a possible answer to why Scotty thought James Kirk was the one who rescued him in the TNG episode “Relics” as well as suggesting that it might have been McCoy who ultimately brought out the “cowboy diplomacy” aspect of Spock’s personality that was revealed in the TNG 2-parter “Unification” where Spock starts secret negotiations with the Romulans.

ELEVENLABS

This short story/script languished on my hard drive until last spring when I discovered (thanks to an introduction from my good friend RAY MYERS in Texas) an A.I. application from New York City-based ElevenLabs that could not only reproduce voices quite accurately but also imbue them with a bit of flair, taking cues from the words of the entered text itself to “act,” showing emotions and other aspects of personality.

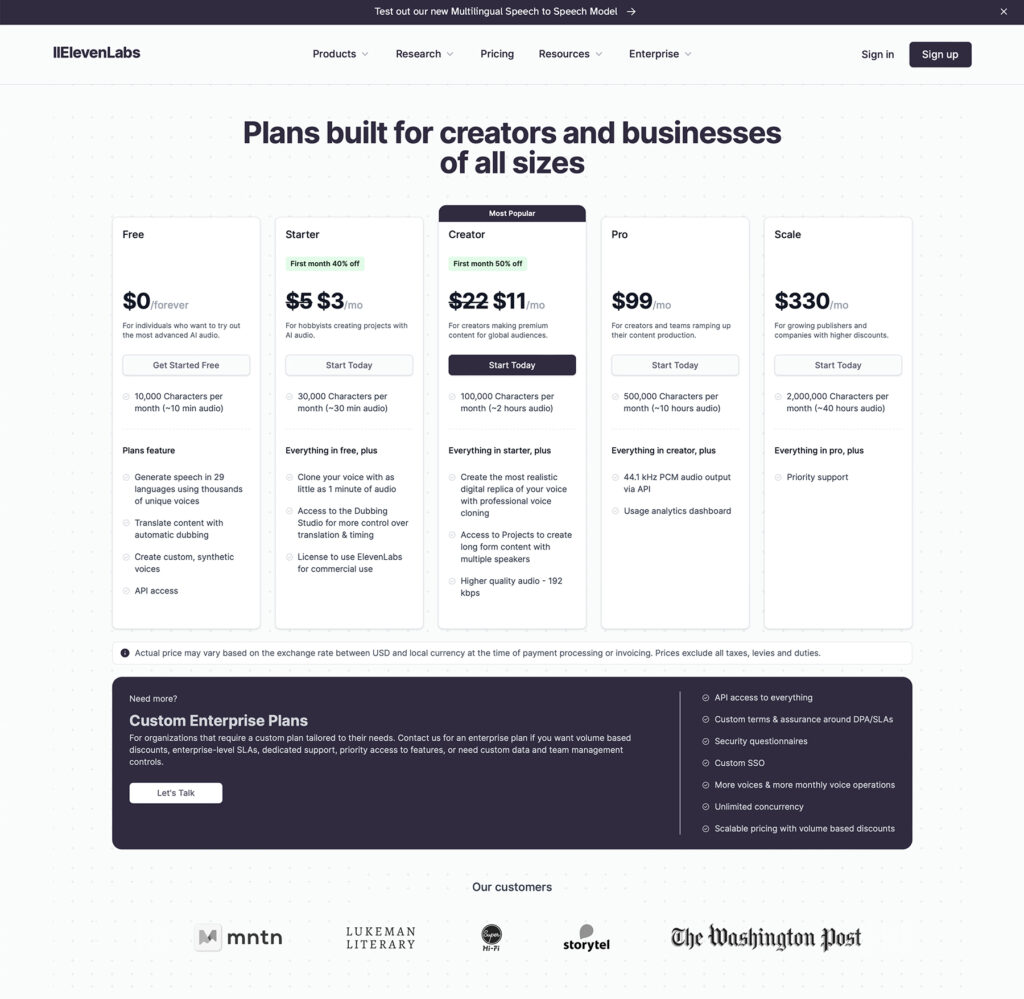

ElevenLabs is a subscription-based service, charging a monthly fee at various levels depending on the bells and whistles the user wants. But what they’re really charging you for is the number of characters (letters, numbers, punctuation marks, spaces) that can be input for creating synthesized speech before you reach your limit. For free, you get 10K characters per month. $5/month gets you 30K characters, $22/month gets you 100K, and $99/month gets you 500K characters each month. I ended up with two months at $99 each to finish my project, but that was mostly because I ended up generating dozens, sometimes over a hundred “takes” of each segment of dialog (more on that shortly).

ElevenLabs offers two paths toward creating customized audio files. The first is to use its own algorithm to generate a myriad of unique A.I. voices that sound realistic. That’s how I created the bartender in the video. He’s just a random character that I asked the website to generate for me based on certain descriptive parameters I entered. He would then say anything I typed into the text box.

Second, and much more impressive, is that ElevenLabs allows you to sample as little as one or two minutes of someone’s spoken voice and then create mp3 files of them saying anything you want them to. Yeah, it’s a little scary to think about, but at the same time, it’s also really cool to play around with. It’s far from perfect, as you can tell from some of the Spock and especially McCoy takes. That said, it’s also surprisingly effective at getting at least close to the sound of the original person’s voice.

So I assembled a few 2 to 3-minute long “clean” samples of both Leonard Nimoy’s and DeForest Kelley’s voices from various sources. When I say “clean,” I mean there needs to be as few extraneous sounds in the dialog as possible. Background music, bumps, bleeps, hums, crowd mummer, applause from convention appearances—anything that distorts the essence of the voice at all is bad. That said, if there’s a stray sound in the middle of decent dialog, just take it out. The voice sample doesn’t need to be made up of complete sentences.

LEARNING THE ROPES

Now that I had voice samples uploaded, it was time to get to work turning my short story/script into an audio drama (as I wasn’t thinking full fan film yet). As much as I would have loved to just copy-paste all of the McCoy dialog into the text box and then do the same with Spock and be finished, it wasn’t going to be nearly that easy!

The first constraint is that the text field is limited to a maximum of 5,000 characters per take. McCoy and Spock each had more than twice that number of characters in my script. But even more frustrating—at least when I created the audio drama it last summer—was that I discovered something that I decided to call “drift.” The longer the take, the more likely the voice would begin to distort as it went on. And the distortion got ever more severe, until what started off sounding like Spock or McCoy wound up sounding like Gollum from The Lord of the Rings or something even worse! I’m told that ElevenLabs has done a lot to minimize this glitch in the year since I first used it, but last summer, it was quite an annoying hassle for me.

It was also potentially a very expensive annoyance, as you’ll recall that I paid for a certain number of characters (letters, numbers, spaces, etc.) for the month, and the counter went up whether I get a good take or a bad one. So if I’d inputted the 5,000-character maximum and there was drift or the voice was a little off, I’d have just eaten away a big chunk of my monthly allotment.

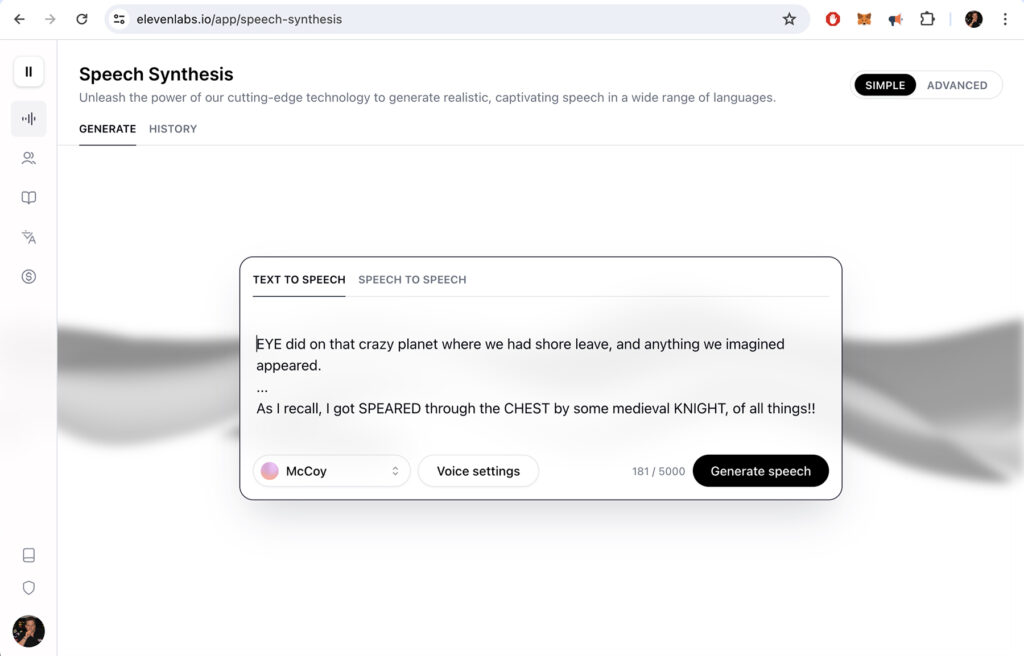

So instead, I would usually opt for no more than 300-400 characters for a single take, which is the equivalent of a few sentences. Sometimes Spock would say something like, “Thank you, Doctor, I would enjoy that…” or “I agree…” and it would be a very fast, inexpensive take. And if it wasn’t quite perfect, I only needed to click the “Generate Speech” button again to get a fresh version of the same line. Sometimes I got exactly what I wanted after only a few takes. Sometimes it took me dozens or even over a hundred(!!!) tries to get something even halfway decent. As such, it was better to grab things in short segments and assemble them later.

Unfortunately, this led to inconsistencies in the different segments I generated. While Spock’s voice remained fairly even for most of his dialog, McCoy’s lines (which were usually much longer) often had sentences that didn’t quite “match” each other. It was still Dr. McCoy, but sometimes the second or third sentence was faster or had a deeper cadence or some other difference from the previous sentence. It was quite annoying but, sadly, unavoidable.

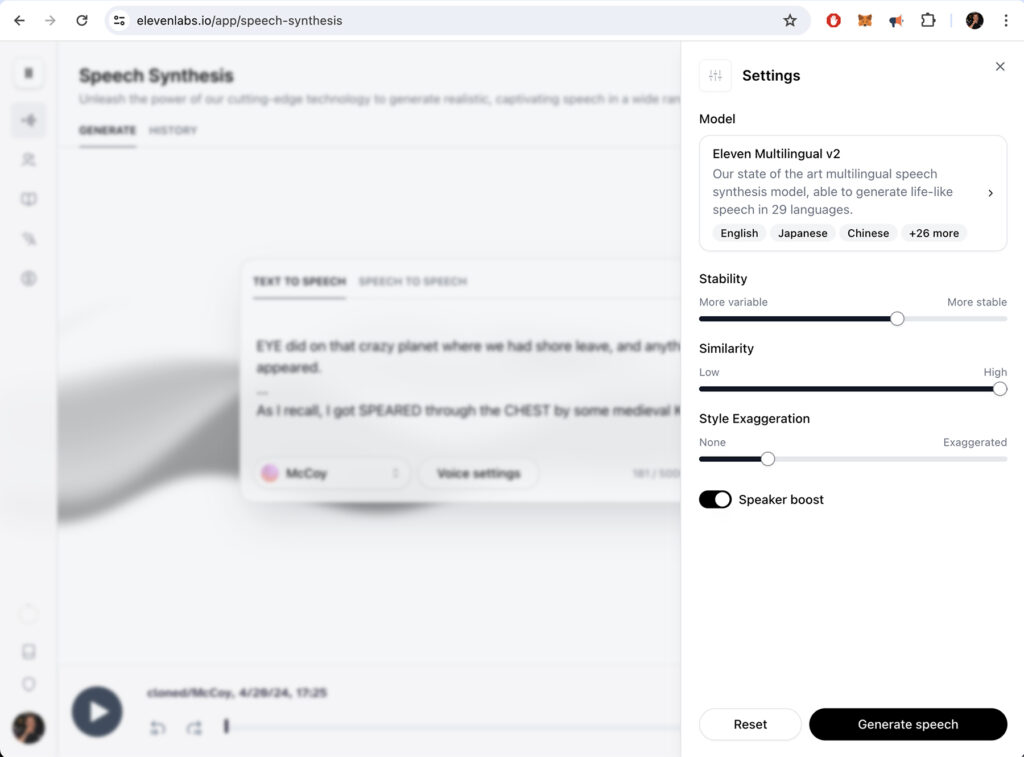

As I mentioned, the mp3 sound files generated are capable of “acting” to an extent. Indeed, there are certain settings you can control via slider bars for controlling just how “emotional” (stable versus unstable) you want the generated spoken sentences to be. Maximizing stability keeps the synthesized voice very close to the original, but the lines are delivered in a very deadpan, emotionless way. This is one of the reasons that Spock’s voice in the fan film sounds so much closer to Nimoy’s voice than McCoy’s does to Kelley’s. McCoy needed to be more emotional (with a stability setting usually between 40% and 65%), and that cut down on the consistency of his voice. While most of McCoy’s lines sound at least a little like the original character—some much closer than others—they do tend to jump around quite a bit. Spock, on the other hand (with a stability setting usually around 85% to 95%), almost always sounds like Spock.

(An amusing side note: when I first generated the audio version of my script and shared it with a few people to see what they thought—not telling them it was A.I.-generated—most of them told me I’d found a really excellent voice actor to imitate Spock, but my McCoy actor wasn’t nearly as convincing!)

PERFECTING THE IMPERFECTIONS

I’ve heard a number of examples of A.I.-generated voices in various places, including a few fan films, and it often seems like the creator generates one or maybe a handful of takes and is essentially done. I, however, wasn’t nearly as “forgiving.” My inner perfectionist would generate take after take after take—sometimes, as I said above, creating over a hundred versions of the same short snippet of dialog (I think I had more than two hundred takes for one line of dialog that ElevenLabs just couldn’t seem to nail until it finally did after hours of trying and retrying).

To give you an idea of exactly how far away some takes could get from sounding anything like Dr. McCoy, take a listen to these unusable takes (one of which actually sounds female!)…

Sometimes I’d get particularly frustrated when a take came out “close” but still not usable for one reason or another…

Eventually, I’d get a few decent takes and use the best one. But even the best takes often needed a bit of “help.” Some were a little too fast or too slow, needed louder volume, had background hisses or hums, or required subtle pitch changes. Occasionally, I’d want to insert a longer pause between certain words or sentences, or shorten a pause. Fortunately, I have a sound-editing program called Abode Audition, and I know it well enough to make the changes I wanted to make.

DIRECTING THE A.I. “ACTORS”

As I said, ElevenLabs has the uncanny ability to “act” by interpreting from the dialog itself the way the lines should be delivered. But what happens when a character is being sarcastic and doesn’t really mean what they are literally saying? Or what happens when there’s not enough information in the entered text to guide the generator to the correct delivery of the line?

Fortunately, after playing with the ElevenLabs application for a while, I discovered that there are actually ways you can “direct” the algorithm by adding words to the dialog that you just remove later in an audio editing program. For example, let’s say that you want McCoy to sound sarcastic. Just add the words, “What I’m about to say is very sarcastic…” at the beginning of the dialog you type in. Want him to sound sad? Have him start with the words, “I feel so sad right now.” You can then delete the extraneous sentence later in a sound editing program.

I also learned other tricks and techniques along the way, like adding extra periods for longer … pauses, as well as writing certain things in ALL CAPS if I wanted the delivery of the sentence to really PUNCH a certain word or words. And if I wanted McCoy or Spock to emphasize the word “I” (already a capital letter), I simply wrote the word “EYE” instead. Lots of tricks I learned!

And then there was the time I just could not get the algorithm to pronounce the word correctly no matter what I tried. In some cases when there was a completely non-English word, like the Klingon moon “Rura Penthe,” I could just write it out phonetically as “Rur uh PEN thay.” And that worked just fine. But then I ran into the word “id” (rhymes with “kid”). It’s from Freudian psychology and is the part of the personality that is entirely impulsive and needs-driven. But as far as the algorithm was concerned, I wanted the computer to speak the letters I.D. (short for identification).

And I just couldn’t make it say “id” no matter what I tried! I needed the word to start with an “ih” sound and end with a “d” sound (and “ihd” just made the computer say “I.H.D.” like an abbreviation). I attempted using the word “idiot” (thinking I cut the “iot” part), but the first syllable blends into the second, and cutting it made the word sound chopped. I ran into the same problem using a rhyming word like “did” or “kid” or “sid.” The first consonant would stick to the “id” part, and McCoy would sound like he had a strange stutter whenever he got to the word in the sentence. There was nothing I could do to make it sound natural.

Eventually, I came up with a rather inelegant solution. I changed the dialog to say “idiot did,” and used an audio editor to remove the “iot d,” as I needed a clean beginning and ending to the word. If you listen carefully, McCoy says “id” three times, and each time there’s a little pop where I spliced the words “idiot did” into “id.” I tried everything to get rid of that pop, but nothing could. So it remains as an audible example that A.I. can’t do everything just yet!

FINISHING UP…MAYBE

As you can probably guess, this project took a LOT of time complete…even for “just” a 15-minute audio drama. I estimate I put in about 200 hours over the course of two months between generating the sound files, choosing the best takes, and then adjusting and finally editing those takes into a final audio drama.

As impressed as I was with the abilities of A.I. to recreate the voices of Spock and McCoy, however, there was still one aspect of the finished audio drama that just wasn’t jelling for me. As I said, there were subtle-but-noticeable inconsistencies in the dialog—especially for McCoy…places where he’d finish a sentence and the next sentence would sound slightly different: more or less raspy, slightly higher or lower pitched, that sort of thing. It felt disjointed and distracting.

But then I had an idea. If I could find some way to animate the audio drama, I could switch “camera” angles when the voice changes occurred. The ear might find that more forgiving if the eye perceived a different image.

The only problem was that I’m not an artist, and the guidelines don’t allow me to pay anyone. Could I possibly find someone to put in that much time and work for free???

In Part 2, we turn an audio drama into an animated fan film…a process that took nearly a full year!

Well done you for now getting 2 fan films under your belt!

That was fascinating (as Spock might say). Yes, there may (soon) be some law bought in to prevent this but, in this case, you’ve done with respect and not for profit – at some cost in fact, going by the subscription fees.

Really interesting to hear how the software does, and doesn’t work. I knew from a documentary on this kind of thing that it’s possible to create a passable impression of someone with limited audio input. But, the more you provide, the better it gets. I guess, prior to reading this, I would have thought it be possible to record the lines as you want them acted out. Feed that into the software and have it deliver them in the voice of the character. But that’s for the future no doubt – or until it’s banned!

Looking forward to more blogs on this.

Interestingly, I often got “line readings” from the algorithm that surprised me to the upside. Usually, I knew exactly what I wanted the sentence(s) to sound like, and just kept generating takes until I got something close to what was in my head. But in some cases, I’d get a take that would make me stop and say, “Hmmmmm….not quite what I wanted, but that was a very interesting choice. It went in a direction that I wasn’t expecting, and I kinda like it.”

In many ways, actors do the same thing. Often, a director knowns the exact way he or she wants the line delivered. But demonstrating that to the actor can be insulting…as in, “Well, if you want me to deliver all the lines your way, how about you just take over the role yourself and I’ll go home?” Actors want their freedom to perform. Directors can direct by describing the mood and motivation, but they should avoid giving line readings themselves whenever possible. And by giving the actor that freedom, directors are often rewarded with performances and line deliveries beyond their wildest expectations. And if the actor doesn’t nail it, the director can always yell “Cut!” and have the the actor try again…and again…and again.

And in the case of AI, the actor can try dozens or even hundreds of times and never get tired or cranky! 🙂

Impressive outcome. Don’t post any of the presidential deep fakes we did that day!!

If you’re still bugged by the pop noise on “id” – let me know – I have an idea!

Too late to fix the pop, I’m afraid. And that presidential deepfake was hilarious…and I’m voting for Biden! 🙂

Jonathan, a very nice article about your trials and tribulations in obtaing the final product. Fascinating and I took special note to many of you attempts and successes achieving the final look, sound and feel. Great work.

Thank you, Dan.