In part 1, I discussed how I used Artificial Intelligence (A.I.) to turn a Star Trek inspired fan script that I wrote back in 2010 into an audio drama featuring the voices of Spock and McCoy. I utilized ElevenLabs‘ voice synthesis algorithm to convert sound clips captured from a variety of sources into a series of back-and-forth dialog between the two characters. Ultimately, I wound up with an approximately 15-minute long audio drama.

Part 2 covered how I managed to take the audio drama and turn it into an animated fan film with the help of an amazing illustrator by the name of MATT SLADE, music composer MATT MILNE, and my longtime childhood friend MOJO. Indeed, in the end, I was the only person involved in this production whose named didn’t start with the letter M! The finished product came out looking like this…

And now the moment that I am certain many of you have been waiting for: the legal and moral questions of “Can Jonathan legally do this?” and “Should Jonathan ethically do this?” These are both complex subjects to tackle. But let’s dive in…!

ATTEMPTING TO GET PERMISSION

Okay, we’ll start out with the obvious: LEONARD NIMOY and DeFOREST KELLEY are both deceased. So who currently owns the rights to their voices? In the case of De Kelley, he and his wife had no children and, therefore, no heirs. California law recognizes only children, grandchildren, and parents to retain the rights to a deceased person’s likeness, and since De Kelley’s parents are long since deceased and he had no children (and therefore, no grandchildren), it appears that the rights to DeForest Kelley’s voice are now public domain.

That leaves Leonard Nimoy, who is survived by his wife SUSAN BAY and children ADAM and JULIE NIMOY. I contacted Adam, who responded, “Hey Jonathan. Thanks for reaching out but I’m not involved with estate issues. You might try [Adam provided me the contact information of the lawyer for the estate]. Good luck with your project. Adam”.

So I contacted the lawyer and spoke to his legal assistant, Jeff, who was very friendly and intrigued by the project. He asked me to write up a brief description of what I was producing and what I was requesting…which was some kind of official permission from the estate to recreate Leonard Nimoy’s voice using A.I.

A few days later, I received an equally friendly response from Jeff which included the following: “[T}o be clear – your request is not being rejected – it is simply not getting addressed. I wish I had better news. The wheels on something like this spin very, very, slowly. I do wish you the absolute best of luck. Love it when people create out of true passion. Keep grinding!”

It appears that the Nimoy estate has no idea what to do with some out-of-the-blue Trekkie asking permission to use A.I. to put one of their deceased clients into a Star Trek fan film. And who could blame them? After all, just researching the relevant caselaw, writing up some kind of agreement for me to sign, potentially revising that agreement based on my feedback (if I had any), and then monitoring the status of the video release to ensure compliance on my end could require several hours of billable lawyer time, costing possibly thousands of dollars to the estate. Who pays that cost?

It’s cheaper to do what Paramount and CBS do: not give “official” permission, per se, but allow fan films to happen without worrying about the hassle of enforcing their guidelines unless there’s some really major infraction. After all, my video that will get—what?—a few thousand views on an un-monetized YouTube channel? Is that really worth a few thousand dollars of legal expenses? And heck, the folks at THE RODDENBERRY ARCHIVES released this A.I. video last year with no statement from the Nimoy estate either:

But this brings up an interesting question: do I or Roddenberry even need to get permission to use A.I. to recreate a deceased actor’s voice or appearance? Is there any law agains doing what we did? Certainly nothing criminal, but are there any civil restrictions in place?

I decided to dig into answering that question, and it appears that Roddenberry and I actually do NOT need permission from the Nimoy estate. Read on…

THE RIGHT OF PUBLICITY

What we’re talking about is a legal concept known as Right of Publicity (ROP), and one of the best summaries of the current state of legislation on this matter exists in this publication from the U.S. Congressional Service from January 29 of this year.

First off, let’s start with the easy part (and this is from the above report): “The ROP is not comprehensively protected by current federal laws.” In other words, I don’t need to worry (yet) about any violation on a federal level. This could change at some point “soon” (you never know with this Congress!), as two bills are currently being discussed in committee to create legislation guiding the use of A.I. to generate images, voices, and/or video of persons both alive and deceased: the U.S. House of Representatives’ NO A.I. FRAUD Act and the Senate’s NO FAKES Act. But until any such bills become law, there is no current proscription at the federal level against using A.I. to make a Star Trek fan film…and laws cannot be made to be retroactive to cover actions that date from before the law went into effect.

So that leaves existing statutes at the state level. Different states have different laws when it comes to ROP—some just have “protections” (like a general right to privacy), and some have no laws at all. About half of the states have actual statutes on the books, and when it comes to whether ROP survives the death of a person, that varies, as well. For example, in Virginia, postmortem rights last only 20 years (DeForest Kelley’s would have expired in 2019 had he lived or died in Virginia, and Leonard Nimoy’s would have still been in effect until 2035). On the other hand, Oklahoma extends ROP one hundred years after a person’s death, and Tennessee has no expiration!

In the case of Leonard Nimoy and Deforest Kelley, both of them lived and died in California, and that is also where I myself live. So we’re 100% under the jurisdiction of California law, and specifically Cal. Civ. Code § 3344. That law grants a 70-year post-mortem status to the heirs and/or beneficiaries of the deceased when it comes to ROP. So those rights are definitely held by Leonard Nimoy’s widow and children…although, again, it appears as though DeForest Kelley’s right to publicity for his likeness has terminated.

Now let’s take a look at exactly what ROP covers…

THE LEGAL EXEMPTION THAT ALLOWS ME TO RELEASE MY FAN FILM

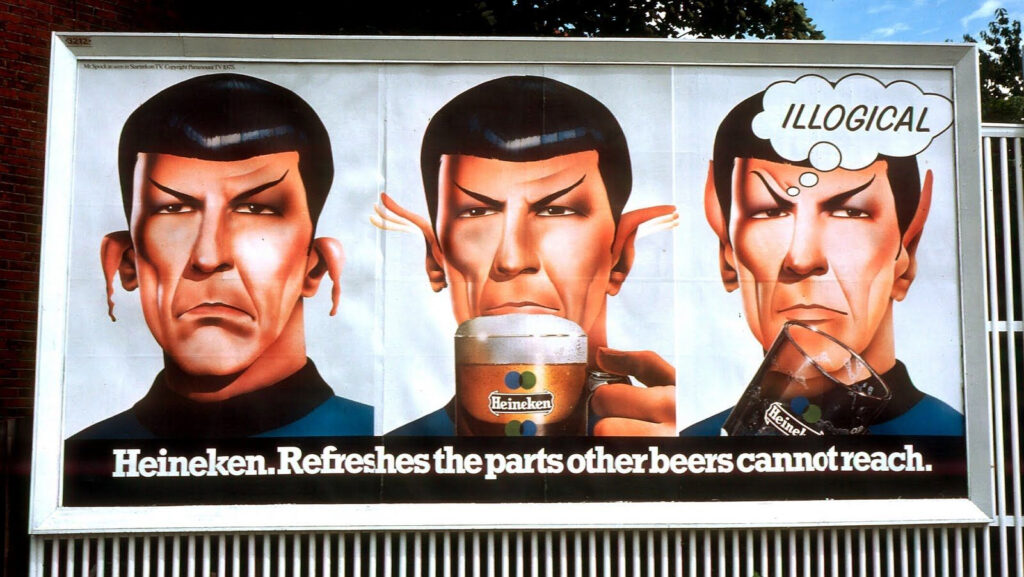

The California Right of Publicity Law was first enacted in 1971, decades before A.I. recreations of people’s voices or appearances were even a dream of what might be possible. As such, the law focuses primarily on using a person’s photo or a recording of their voice or face to imply a commercial endorsement. Indeed, Leonard Nimoy himself was involved in a lawsuit in the mid-1970s when Paramount licensed his image to Heineken Beer for a billboard without reimbursing Nimoy or even seeking his permission.

Nimoy’s concern back then wasn’t simply over the unreimbursed use of his image; it also had to do with the sexual innuendo of the ad reflecting badly on him and his beloved character. That said, the lawsuit disappeared shortly thereafter when Paramount approached Nimoy reprise his role of Spock in a relaunch of Star Trek (what became Star Trek: The Motion Picture in 1979). Nimoy refused to even read the script until Paramount agreed to settle the lawsuit and pay him, which they promptly did.

Then in 1988, Civil Code section 990 was added to the California legal statue specifically dealing with ROP for deceased persons. I won’t bore you with all of the details, although they are included within the above link. However, there is one clause which I would like to pull out and highlight:

(n) This section shall not apply to the use of a deceased personality’s name, voice, signature, photograph, or likeness, in any of the following instances:

1. A play, book, magazine, newspaper, musical composition, film, radio or television program, other than an advertisement or commercial announcement not exempt under paragraph (4).

2. Material that is of political or newsworthy value.

3. Single and original works of fine art.

4. An advertisement or commercial announcement for a use permitted by paragraph (1), (2), or (3).

I added the underline to the word film myself. Also, An Absent Friend could potentially be considered as a “3. Single and original work of fine art.” After all, it is original, a one-of-a-kind project, and intended to be a work of creative art.

In this way, it seems the California law as written and ratified in 1988 specifically exempts my and Roddenberry’s fan films from any legal liability for using the voice(s) and/or face of a deceased individual. This would not be the case were we to use the voice of a living person, by the way, but I certainly was never intending to do that, and I doubt that Roddenberry will be doing so either.

Of course, once the lawmakers catch up to A.I., this could all change in a heartbeat. Indeed, the California State Assembly is currently debating AB 1836, which specifically addresses post-mortem digital recreation rights and would impose a statutory fine of $10K (which I certainly couldn’t afford!) instead of the current fine of $750 (which isn’t nearly as much of a problem). However, this proposed legislation carries with it a number of first amendment concerns which are being written about in the media and could potentially be challenged in court if passed.

That said, I’ve decided not to wait until AB 1836 comes out of committee. To be on the safe side, I’m releasing An Absent Friend now, before any new laws are passed. And who knows? Maybe my fan film will be discussed by the California legislature or even the U.S. Congress as an example of one of the ways that A.I. could be used to express creativity in a purely non-commercial, non-hurtful way…since my sole intention is to honor these two actors rather than exploit them for profit, use them for self-promotion, or try to harm either of their reputations. If anything, one could potentially argue that this project is intended for educational purposes, as this extensive and detailed (i.e. loooooong!) 3-part blog series describing the method, process, and legal/ethical questions associated with creating an A.I. animated fan film could not exist without An Absent Friend to provide the topic and specifics of discussion.

ETHICAL CONCERNS ABOUT A.I., DECEASED ACTORS, AND FAN FILMS

So that answers the question of “Can Jonathan legally do this?” What about “Should Jonathan ethically do this?” After all, A.I. is making a lot of people—including actors, artists, musicians, writers, and other creatives—VERY nervous right now. Will they literally be replaced by computers within the next few years? It’s definitely something to worry about, and indeed, my artist for the film, Matt Slade, is finding it increasingly difficult to get illustration gigs. Ironically, this A.I. project gave him some artistic work to do to pad his portfolio and get his name out there (since the CBS/Paramount guidelines preclude anyone from getting paid to work on a Star Trek fan film).

Speaking of the guidelines, someone who saw an early version of this fan film asked me why I didn’t hire talented voice-actors to imitate Spock and McCoy and skip the A.I. entirely. That way, I wouldn’t be “taking work away” from dedicated actors. Of course, what I’m really doing is taking UNPAID work away from dedicated actors. And most actors do want to be paid. Those willing to work for free likely wouldn’t have the skill or ability to convincingly imitate Spock and McCoy.

Regardless, however, the main reason I tackled this project wasn’t simply to turn my script from 2010 into a Star Trek fan film. I could have done that with actors any time in the last decade and a half. No, I wanted to find out what A.I. voice synthesis was capable of and how one might go about about creating a fan film with it, since it’s pretty obvious that A.I. isn’t going away anytime soon…and probably not ever. Simply avoiding it and pretending it doesn’t exist—even if for supposedly “ethical” reasons—won’t change the inevitable march of history and technology in that direction. And so I wanted to take a crack at it in order to learn, and by learning, perhaps also to teach others.

You see, the true purpose of this project, much like my previous Star Trek fan film INTERLUDE, was to blog about it. I’m a blogger; it’s what I do. With Interlude, I wanted to learn about and share with my readers the experience of making a Star Trek fan film from conception through budgeting, crowd-funding, pre-production, production, and ultimately into post-production and eventual release.

In the case of An Absent Friend, I wanted to explore A.I. voice synthesis, see what worked and what didn’t, discover some tricks and techniques, and ultimately share those with others through this three-part blog series. And of course, I needed the finished fan film up on YouTube in order to display the things I’ve been talking about.

As for the question of how a deceased Leonard Nimoy or De Kelley would feel about a Star Trek fan using A.I. to bring their characters back to life, there’s no way to know. And one can’t simply assume that they’d be against it. Personally, I think De would have been totally on board, as he did love the fans and would probably feel excited that Dr. McCoy could continue on as part of the Star Trek legacy. And as I said above, Adam Nimoy wished me luck with the project, which is a far cry from “Don’t you dare use my deceased father’s voice!” But again, we just can’t know how either man would have felt, and therefore, we shouldn’t assume.

And so, for me, the answer to the question of “Should Jonathan do it?” comes primarily from my inherent desire as a blogger to explore, learn, and teach others. I apologize to those who eschew A.I. and just wish it would go away. But as I said, that does not seem to be happening. So rather than fighting the future, I have decided to get a better idea of what A.I. is all about…and make a little Star Trek fan film with it.

Will I do any more of these kinds of animated A.I. voice projects in the future? Most likely no. An Absent Friend took nearly a full year to complete, and now that I’ve done it, I feel I can move on to something else. Will that something else be A.I.? Who knows?

For right now, though, I’m just going to return to blogging about other people’s fan films.

To me this is a double edged sword personally . The question becomes when will it go too far?

Good question…and I have no idea. However, as I said, lawmakers are now working to address some of the most troubling issues. As with anything that involves free speech versus limited speech, the law must be very careful. It’s legal to say racist things (sadly), but it’s not legal to provoke racial violence. Where and how do we draw the line? The same will be (and is!) true of A.I.

Thank you for the blog posts showing not just how, but also why this approach was taken. You’ve also taken the time address the concerns about AI voices.

Majel Barrett recorded a large amount of computer dialogue with the intent of it being used after her death. I have no doubt that this has since been used to train an AI for further dialogue flexibility.

Barret probably would have been fine with fan films using an AI voice based on her, but we don’t know.

Personally I am uncomfortable using AI voice without the person’s express permission, alive or dead.

Ultimately whilst I would not use AI voice in my own fan works, it is not my place to dictate what others should do. The decision on whether to use AI voice based on real people should be up to the fan film maker – if they are fine with it then I am not going to tell them not to.

Are there AI voice services out there where there is explicit permission from the person they are trained on?

Alternatively are there AI generic voices (i.e. not based on one person), that can do the quality of a reproduced voice?

Little known fact: when Majel recorded the Enterprise computer voice, I wrote the script for her (70 pages…took her 4 hours!) and directed the session at her home in Bel Air in the study room where Gene used to do all of his work. That was SO cool. And Majel, who had already had her stroke before then, was amazing. She did the whole four hours with only short breaks of a minute or two when airplanes were passing overhead.

As for your questions, I don’t think there are any services (yet) where they track and keep permissions from people who want their voice used for A.I. But it’s an intriguing idea…like stock photography where an artist gets a small payment for every use of their photo.

That said, your second question might negate your first one. Eleven Labs has the ability to generate original A.I. voices of any kind–male or female, young or old, accents, etc. In fact, my bartender was one such A.I.-created voice!