In the summer of 2016 when the AXANAR infringement lawsuit was still in full swing, I drove to the Federal Courthouse in downtown Los Angeles to attend a hearing of the Ninth Circuit in that case. I was the only guest in the “audience” and the only person in the courtroom other than the clerk who didn’t have a law degree!

Nearly all legal proceedings in America are open to the general public, but few citizens avail themselves of this right because—for non-lawyers and non-participants—most of these proceedings are nigh incomprehensible and boring.

But I was personally invested in the Axanar case and found the hearing absolutely fascinating! In fact, I suspect that, had more Axanar supporters lived close to downtown L.A. and didn’t have work commitments, they would have flocked to watch the trial…had the case not settled.

Now the COVID-19 pandemic has offered a unique opportunity to watch Federal Court hearings remotely. The judges and lawyers are all working from separate locations and dialing into a video conference, and those proceedings are being broadcast live to YouTube so the public can observe. The conference videos are also being recorded and kept available on YouTube. Nothing like this has ever happened before! [CORRECTION – Oops, got that one wrong. Then Ninth Circuit (and possibly some other courts) has been streaming oral arguments since 2014.]

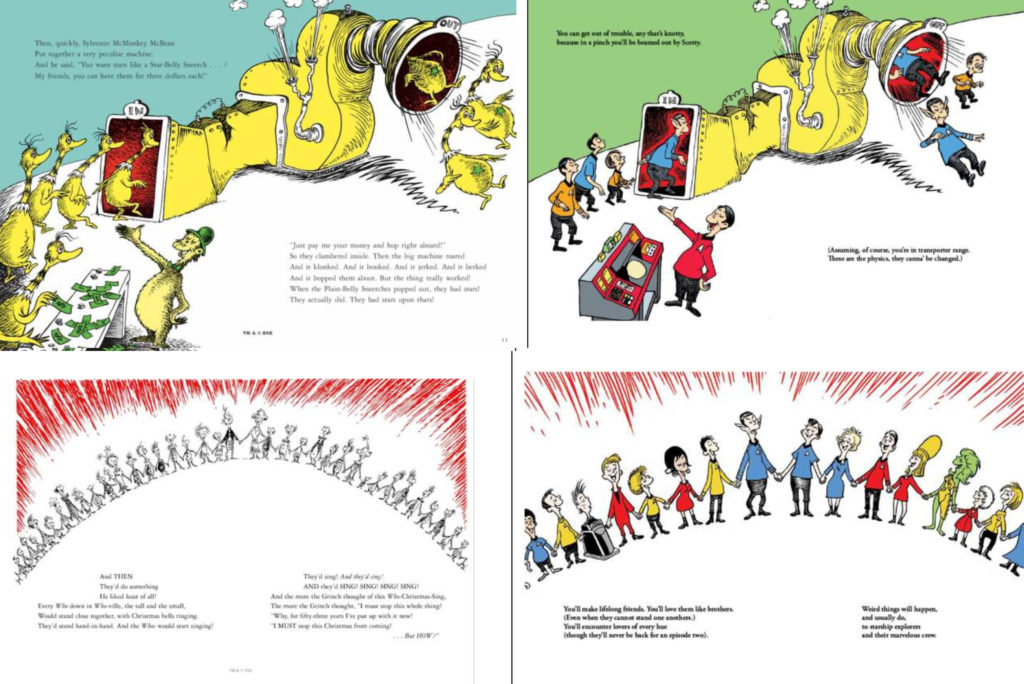

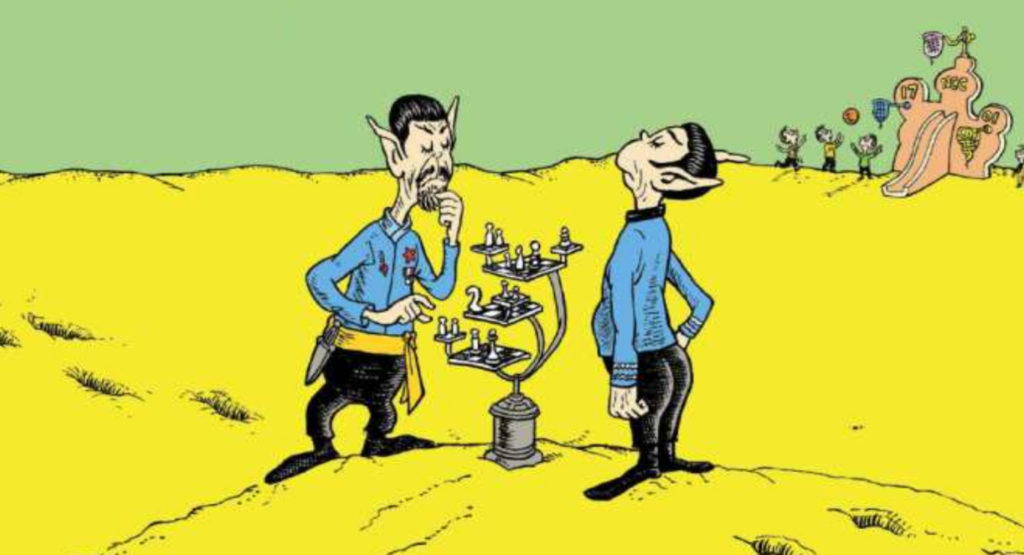

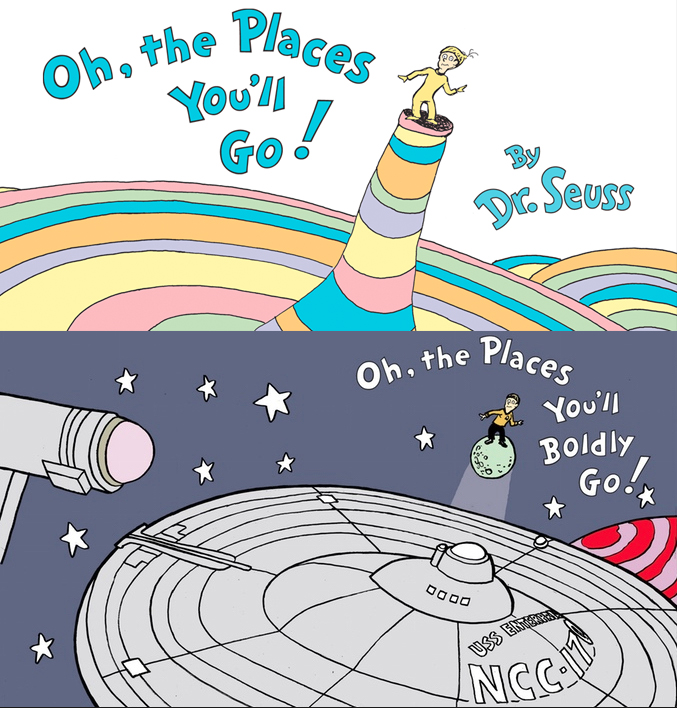

As many of you know, I’ve been closely following the infringement lawsuit where DR. SEUSS ENTERPRISES (DSE) has sued COMICMIX and author DAVID GERROLD, artist TY TEMPLETON, and publisher GLENN HAUMAN for violating DSE’s copyright in trying to publish Oh, The Places You’ll Boldly Go! mashing up Star Trek and Dr. Seuss.

Long story short: DSE lost. (Long story long: read this.)

With a pre-trial summary judgment, Judge JANIS SAMMARTINO ruled that “Boldly” (as it was shortened) qualified for First Amendment protection on the doctrine of Fair Use. That was in March of 2019. In August, DSE filed an appeal of that decision. (And here’s a blog explaining that in detail.)

The thing about an appeal is that you can’t just say, “Hey, we didn’t like that verdict, so we want a do-over with a new judge!” Nope, you can only appeal if you feel the first judge made a mistake in interpreting or applying the law in some way (other than just deciding against you.)

In DSE’s case, the biggest mistake they felt was made by Judge Sammartino was in determining that they (DSE) had to prove that they would suffer financial harm if Boldly were to be published and sold. DSE felt that ComicMix should have had to prove that DSE would not be injured by the mash-up. But because the district judge reversed the direction of burden of proof, and DSE failed to meet that burden, they lost and Boldly was ruled Fair Use. (DSE also felt that Boldly wasn’t transformative and also used too much of the original Dr. Seuss source material, which they contend should overturn any Fair Use ruling.)

On Monday morning in Seattle (and in call-in locations elsewhere), the three-judge appeals panel listened to oral arguments from the two lawyers representing DSE (Plaintiff) and ComicMix (Defendant), and this is what happened…

If you don’t want to watch the 34-minute video, I’ll be supplying some play-by-play highlights below. But I do suggest you take a look, as it shows how prepared lawyers have to be, and how much they need to think on their feet.

To truly appreciate the nuances of what’s on this video, it’s important to first understand a few important things…

- The three judges have already reviewed hundreds and hundreds of pages of filings and evidence and arguments and motions concerning this case. They are unlikely to learn anything truly “new” during this proceeding. The goal here is for the lawyers to make their arguments in person and for the judges to ask for clarifications and (if necessary) challenge the lawyers’ conclusions.

- Unlike criminal cases or trials you might see on TV—where the judge doesn’t speak unless there’s on objection or at the end when there’s a verdict—with a Federal civil lawsuit, the judges interrupt constantly!

- Judges might come into oral arguments already predisposed to support the plaintiff of the defendant. They still keep an open mind (or should!), but often they will “challenge” a lawyer on the side they want to win in order to pitch them a softball question that they can easily answer. This is usually an opportunity to help the lawyer argue a point that needs a little extra punch to persuade the other two judges.

- For an appeal, judgment does not need to be unanimous. 2-1 works just as well as 3-0.

- Speaking only very generally, plaintiffs’ appeals for reversals of judgements succeed only about 18% of the time. Also, the Ninth Circuit Federal Appeals Court is seen to be one of the most liberal in the nation and tends to favor the “little guy” over the big “corporate bully” much of the time. That said, it all depends on which judges are randomly assigned to your appeal.

In this case, the identities of the three judges are very telling. The first two—Judge M. Margaret McKeown (appointed by Bill Clinton) and Judge Jacqueline Nguyen (appointed by Barack Obama)—are liberal judges. In fact, during the Obama administration, McKeown’s name was being bandied about as a possible Supreme Court nominee replacement for David Souter in 2009 (the spot ended up going to Justice Sonya Sotamayor). And if you paid any attention to the recent Stairway to Heaven copyright infringement case, Judge Mckeown wrote the final Skidmore v. Led Zeppelin appellate opinion. That decision sharpened the Ninth Circuit’s substantial similarity test, potentially making it more difficult for DSE to prove that ComicMix “copied” too much from Dr. Seuss.

On the other side of the political aisle is the third judge, N. Randy Smith, appointed by George W. Bush in 2006 and confirmed by the Senate 94-0. (Remember days when bipartisanship used to happen?). While it’s not at all certain that he’d side with DSE, he is a conservative judge. So just on the face of it, I’d predict a final ruling of 2-1 in favor of ComicMix.

But is that the way it looked from the actual hearing? Interestingly enough, I think the answer is YES. Below is my take on moments where the judges asked some of those “help-my-guy-make-his-argument-better-in-order-to-convince-the-other-two-judges” questions. So if you don’t want to watch the whole video, just skip to these time-codes:

2:00 – Plaintiff’s attorney STANLEY PANIKOWSKI is barely 90 seconds into his presentation when Judge Smith interrupts him asking him to clarify a point about a possible mistake that the district court made in placing the burden of proving financial harm onto the plaintiff. What a coincidence that he’d ask such a question early on, as that’s the main complaint in DSE’s appeal!

Fair Use is supposed to be an affirmative defense, meaning the burden is on the Defendant to prove that what they did isn’t infringement. And that would include showing that there would be no significant financial harm to the plaintiff. But in her summary judgment, District Judge Sammartino ruled the opposite, that the burden of proof then shifted to the Plaintiff to show there would be significant damages, which they failed to do. So almost from the get-go, it seems pretty likely that Judge Smith is on the “side” of DSE in believing there was a mistake made at the district level.

6:30 – Now it’s Judge McKeown’s turn to interrupt Panikowski, and she’s playing a bit of 3D chess here. Knowing that DSE isn’t just asking for the case to be remanded back to Judge Sammartino for a re-do—they actually want her judgment completely overturned and for the appeals judges to rule that there was infringement and end the lawsuit in DSE’s favor—McKeown is asking how they expect the appellate judges to arrive at such an about-face conclusion when the defense contends that they haven’t infringed. In other other words, she’s going on record as saying this might be a bridge too far, and a ruling of infringement is not appropriate at this appellate stage, if at all. But please respond anyway, counselor.

This is where McKeown got what she wanted, which was an unavoidable concession by the Plaintiff’s attorney of a willingness for the case to simply be remanded back to the lower court to the tried again. Of course, DSE would prefer the home run, but a hit to any base would still be a hit.

Interesting enough, DSE’s argument (a flimsy one, in my non-expert opinion) is that in winning the case on Fair Use, ComicMix never actually said that they weren’t infringing. Therefore, if the appellate judges rule there was no Fair Use, then ComicMix must be infringing, right? However, ComicMix was never stupid enough to say, “Okay, we’re infringing, but hey, Fair Use, right?” So DSE is swinging the bat, but this pitch might ultimately be a foul ball.

13:39 – Mckeown interrupts Panikowski to ask if he’d like to go on making a long speech or reserve the remainder of his time for rebuttal. This accomplishes three things: 1) it stops him from hammering home a strong point, 2) it ends his “at bat” and turns the argument over to the defense, and 3) paints the judge in a good light by it looking like she’s trying to help the Plaintiffs not use up all of their time.

15:15 – McKeown interrupts Defense counsel DAN BOOTH by saying she doesn’t understand how Boldly is a parody. Oh, really? The judge knows that the lower court ruled that Boldly was NOT a parody. Had Judge Sammartino determined Boldly to be a parody, the case would have been over right then and there because parody is protected speech. And if Booth can convince the appellate court that Sammartino was wrong to say it wasn’t a parody, then it’s a home run for the Defense, as the higher court can rule the mistake was in not acknowledging Boldly as a parody in the first place! So this softball pitch is allowing ComicMix the opportunity to potentially hit it out of the park themselves. Granted, home runs are still hard to accomplish, but a chance is a chance.

18:30 -McKeown continues making her chess moves. She knows that it could be argued that ComicMix got caught with its hand in the cookie jar and quickly said, “Oh, it’s a parody! Can’t touch us!” So she gives Booth the opportunity to establish that, no, that wasn’t the case at all. In fact, she even asks when they decided to use Dr. Seuss’ Oh, The Places You’ll Go! as a single source. McKeown isn’t dumb; she knows that they didn’t only use Go! There are drawings reminiscent of multiple Dr. Seuss works (and not exact copies), including other stories like The Sneeches and Horton Hears a Who.

Booth reads her mind and affirms that the idea of this being a parody was there almost from the get-go, and that Gerrold, Templeton, and Haumann always intended to use multiple sources in order to convey the feel of Dr. Seuss, as that is one of the components of a “mash-up,” combining two or more familiar things into a new transformative work. In order to combine them, the work has to make the elements of each source recognizable. It’s a part of the new art form.

20:20 – We finally hear from Judge Nguyen! Her question is also a softball made to sound like a challenge. She asks if there’s evidence that ComicMix did, in fact, seek to create a parody from the very outset. One would assume that she’s already seen the evidence (mostly back-and-forth e-mails). And Booth’s response is that, although there was no mention of parody in the very first e-mail, parody was mentioned in the response, establishing that parody was pretty much in the creators’ minds nearly from the point of inception.

Forty seconds later, McKeown jokes that after they said parody, they added “…those people in black robes might disagree with us.” But she’s not trying to be nasty about it. She knows that was said in jest, and Booth reads the room and acknowledges that the creators were tongue-in-cheek about that in the marketing text on the Kickstarter page. He also makes certain to mention that the Kickstarter makes sure to mention publicly that this is a parody and a work of Fair Use and a mash-up—a “parody mash-up.” They were consistent in this belief all along and didn’t suddenly come up with the “excuse” once they were sued.

21:30 and 23:20 – McKeown is concerned that the district court judge may have given Boldly too much leeway when she called it “transformative.” Did Judge Sammartino confuse “transform” (which Boldly did do to all the Seuss illustrations it used) with “transformative”? Might Boldly really be just a derivative work (and therefore infringing) with some transformed pictures? Booth’s answer to this, I believe, is his best “thinking on his feet” moment. Judge Sammartino said that something can be BOTH derivative AND transformative (they aren’t mutually exclusive), but Boldly isn’t simply derivative. It doesn’t supplant or replace Dr. Seuss, as someone looking to buy a Dr. Seuss book would not be satisfied with a copy of Boldly. It’s a completely different (and therefore, transformative) work.

24:45 – McKeown continues doing all the heavy lifting today by asking the question that allows Booth to focus on that most important piece of undercutting DSE’s only really strong argument: that there’s potential harm to DSE because allowing Boldly to be published could lose DSE many other licensing opportunities for similar mash-up projects. McKeown certainly knows the answer to her question because it was plastered all over just about every brief filed by ComicMix: DSE doesn’t allow mash-ups. Their own style guide to licensees forbids incorporating characters from other worlds with characters from Seuss’ worlds. The Cat in the Hat meets Spider-Man or Horton Hears an R2 Unit simply would never happen. (Booth doesn’t give those specific examples; I made those up myself.) And while DSE has made rare exceptions to letting characters from outside franchises meet Seuss characters, DSE never ever does mash-ups. Booth also adds in an important reminder: a work doesn’t necessarily need to be a parody in order to be Fair Use…only transformative.

27:45 – Judge Smith, who hasn’t gotten a word in edgewise in more than 25 minutes, finally inserts an important challenge question…although it’s the same point he made back at two minutes. What case does ComicMix cite to support Judge Sammartino’s ruling to shift the burden of proof on financial damages from the Defense to the Plaintiff? Here Smith is trying really hard to justify at least remanding the case back to the lower court with an instruction to shift the burden of proof back to ComicMix to prove that Boldly will NOT harm DSE. That doesn’t necessarily lose the case for ComicMix, but it does make getting a Fair Use ruling more of a toss-up.

Booth tries to list all of the examples in the past where DSE wasn’t harmed by an unlicensed parody work, but Smith follows up by hammering on the potential harm of DSE losing possible future licensees who choose to follow ComicMix’s example of claiming Fair Use. Booth quickly points out that Judge Sammartino called that a “doomsday scenario” which was too speculative to be considered evidence of actual harm.

30:00 – McKeown chimes in and doesn’t necessarily agree with Smith but doesn’t contradict him either. It’s actually a good point that Smith is making. Fair Use is an affirmative defense, meaning the burden of proof is on the Defendant. In the case of Fair Use, there are four factors the Defense must prove, and Judge Sammartino shifted one of those to the Plaintiff. So McKeown asks why, if the district judge could shift one of the factors to the plaintiff, why not shift all four? Booth provides an interesting response that is probably more suited to a mock debate in a law school class, and it seems as though McKeown appreciates the opportunity for a refreshing little bit of academic repartee.

And it is at this point that McKeown notes that they’ve let Mr. Booth exceed his allotted time because he’s made some very interesting points. I suspect that, at least to McKeown (and possibly for the other two), this is a more enjoyable case than most. The previous case involved a $111.4 million industrial environmental clean-up in Montana by two major corporations. This case involves Dr. Seuss and Star Trek. Which case would YOU rather listen to? Booth respectfully ends his presentation, and Mr. Panikowski takes a final two and a half minutes to wrap up the Plaintiff’s presentation.

So what happens next?

In the Federal system, appeals courts can take as much time as they want after oral arguments to render a decision. So this case could wrap up in a day, a week, a month, or a year or more (but probably not that long).

Most likely, either ComicMix will win again or else the case will be sent back to the lower district court (same judge) with instructions on how to address the previous “mistake.” I believe that it’s highly unlikely the appellate court will overturn the Fair Use ruling AND also rule infringement and award damages to DSE.

In either case, the losing side is welcome to appeal the decision one final time to be reviewed by the entire Ninth Circuit (en banc). There are still more liberal judges on the Ninth Circuit than conservative ones, so this could be another fool’s errand for DSE if they lose this time. (And if they lose again, they can always appeal to the Supreme Court…although they tend to reject about 98-99% of the cases brought to them. So good luck with that.)

However, DSE has deeper pockets than ComicMix. So unless the appellate court issues some ruling for the Defendants’ legal fees to be paid by the DSE, an en banc appeal might be beyond ComicMix’s ability to fund (unless fans help support another crowd-funder).

For this same reason, if ComicMix loses the appeal and the case is remanded, it might be best to just let things proceed back at the district level (likely a fast resolution) than spend another year or three in the appeals process.

Whatever happens, folks, I’ll keep you posted!

Fascinating insight into our judicial system, as always. Thank you for wading through all this. Can’t imagine how many hours you have put in.

Well, it’s this, helping Jayden with virtual school, watching CNN, and emptying the dishwasher. 🙂

My attorney son has been handling the telephonic bankruptcy court hearings for our law firm recently, and comments that they take longer than in-person hearings, as the participants are often talking over each other. I saw an article in the ABA Journal email newsletter this week about video court hearings, where one judge was complaining about attorneys not bothering to wear court-appropriate attire for the video hearings (things like appearing in bed, still under the covers, or in a T-shirt and blue jeans). Just because one isn’t in the same room as the judge, doesn’t mean that the judge can’t see what you’re wearing!

And yet, you’re never allowed to see what the judges are wearing under their robes. An in-law of mine is a federal tax judge and has admitted to wearing sweat pants more than once in court. 🙂

Hi, Jonathan. As you commented on The Illusion of More and invited me to comment here, I shall, though I hope you do not mind some constructive criticism on a few points—one non-attorney legal observer to another. And as a nitpicky note, the ability to watch oral arguments is not new since the pandemic. Not all courts offer the same access, but the Ninth Circuit has been streaming oral arguments since 2013. Onto the legal matters …

As a general note, I would caution against reading too much into the motives of judges, including assumptions based on left/right ideology, at least where copyright is concerned. Liberal lioness Justice RBG is the most prominent, pro-copyright (pro author) judge in the United States. More broadly, though, I think you will find that copyright is an area of law that is not so obviously painted by political color as we tend to see in other matters. Hence, I would critique your overall approach in which you ascribe motive to each judge on the panel, particularly where your analysis does not wholly comport with procedure or case law.

I will not go point-by-point, as you have done in your extensive post, but thought it worth trying to clear up some basics. The main matter before the appeals panel is whether the DC erred in its fair use analysis, and I strongly suspect they will find that it did. Maybe even unanimously. The questions asked by the judges went almost entirely to either the first or fourth factors of the fair use test, which were the two big areas of concern for any copyright interests watching this case, not just DSE.

For instance, that issue of burden is tied to the fact that the district court committed the too-common error of failing to consider the “potential” market of the rights holder. The rights holder does not need to have already entered a particular market in order for the court to find harm has been done to the potential value of that market. The DC erred (in the opinions of many) by holding that “Boldly” is not a derivative work, and then it made matters worse by shifting the burden to DSE to prove market harm. This is not supported by case law.

It is incorrect, though bold, to assert that a work can be both derivative and transformative, in a legal sense—and this is why “transformativeness” is such a bugaboo concept. A derivative work is always transformative (in layman’s terms) by its very nature. But when “transformativeness” is improperly assessed in regard to the first factor of fair use, the court can end up transferring the derivative works right to a defendant simply because the defendant made a particular derivative work before the copyright owner did—or against the owner’s wishes.

In your paragraph on that subject, you sow some confusion by citing market substitution in context to derivative works. If “Boldly” is held to be a derivative work, it is infringing full stop, as you state, no matter what effect it could have on the market for “Go.” Separately, the fourth fair use factor considers whether a particular use can serve as a market substitute. That consideration need not be assessing a use that constitutes a derivative work. Sometimes, courts have erred by holding that simply using a work in a different context does not harm the market for the original. Thankfully, these have usually been overturned on appeal.

Assuming the panel enters a judgment of no fair use, they could remand for trial on the claim of infringement, at which point ComicMix would have to convince a jury (assuming it gets that far) that “Boldly” does not infringe the works protected by DSE. ComicMix would have to prove how “Boldly” does not infringe any of the rights under §106, namely the derivative works right; and this would probably be very difficult to achieve. This is because any ordinary observer will likely perceive that “Boldly” copies Seuss too extensively.

Anyway, these are just a few points that jumped out at me, and I do not mean to criticize your efforts overall.

Thanks for the equally thoughtful reply, David. For those who don’t know, David and I have been going back and forth on his blog site this morning, and it’s worth reading his take on this case, as well as mine (and his entry much shorter!)…

https://illusionofmore.com/things-creators-can-learn-from-seuss-v-comicmix

I wasn’t aware that the Ninth Circuit has been streaming orals for seven years, so thanks for that correction. I’ll leave the mistake in the blog but add in a note to indicate the correction.

I agree that the elephant in the living room here is the district court’s decision to shift the burden of proof on the fourth factor to the Plaintiff. I can certainly see remanding the case back to the DC with instructions to shift the burden back to ComicMix, but I don’t necessarily agree that the appellate judges will rule there was no Fair Use at all. The game is still afoot. ComicMix has been arguing that there is no evidence of potential harm, and so the judges could consider those arguments and still decide in favor of Fair Use or they might simply let the kids fight it out in the lower court. For the first 350 years of the existence of Fair Use, the ultimately determination had been made by juries as a matter of fact. It’s only been in the last 30 years or so that judges have usurped this authority from juries by determining Fair Use through summary judgments as a matter of law. No bueno, say I. Personally, I prefer the first three and a half centuries to the last quarter century, as it spreads the subjective interpretation of the four factors to a larger and more representative sampling of the People than a single (or three single) elite law school graduate(s).

And I totally think a work can be both derivative and transformative. That is the whole basis of the mash-up. If it’s not derivative, then how can one even tell that it’s a mash-up of two or more recognizable sources? As I said on your blog, Andy Warhol derived his famous painting from a Campbell’s soup can. But he also transformed it. Legally, the Fair Use doctrine allows for this. “Transformative uses are those that add something new, with a further purpose or different character, and do not substitute for the original use of the work.” Andy Warhol’s soup can paintings could never substitute for actual Campbell’s soup. And someone wanting to give a graduate the gift of a story about a young child conquering his fear of the world in order to explore its many offerings would not be satisfied giving that graduate a book about Starfleet officers and Klingons (unless the grad is a Trekkie, which the vast majority are not). In other words, don’t count out Fair Use just yet!

As for reading the tea leaves on the judges’ predispositions, that’s just part of the fun for me in watching an actual hearing! Admittedly, I’m not a lawyer nor a legal expert. I’m a blogger with a penchant for looking at these types of proceedings from a lay-person’s perspective (although one who has thoroughly followed and researched this particular case and a few like it). I do contend that judges try to “help” the side they prefer or challenge the other side with carefully-designed questions, and I’ve seen the SCOTUS do that quite often. And in my eyes, Judge Smith seemed to already have his mind made up in this case. McKeown seemed much more open to Defense arguments and threw mainly softball questions at Mr. Booth. You are correct in that this doesn’t mean she’s a lock on giving ComicMix a pass on everything…and liberal doesn’t necessarily mean being against copyright protection. But I was analyzing more the questions themselves and what it seemed like they were intended to accomplish. I might have gotten it completely wrong, but it was a stimulating exercise to watch the video carefully and try to read the poker faces and chess moves.

Anyway, like all legal cases when the juries or judges go off to deliberate, all we outsiders can do is conjecture and wait. My hope is that ComicMix comes out of this with a “win” because I feel that mash-ups are indeed a new art form that add fresh and unique voices to the rich chorus of expressions we enjoy as a nation and a world. I don’t feel that all mash-ups should automatically be given First Amendment protections, but neither do I feel that copyright ownership is expansive and absolute. We have a gray area that invites case-by-case consideration…and this is one of those cases!

Thanks again for the mental workout, David. All the best to you!

I appreciate the exposition and digression from pandemic news. And hopefully this ability to watch the legal profession at work will continue past the current lock down.

And based on how often those who watch SCOTUS at work can predict the outcome based on questions, it was not surprising to see you doing the same thing here.

We’ll see how you did.

If CNN can do it, then so can I! 😉